ChatGPT-4o Plays Telephone: Tracking Generation Loss Over 100 Generations of Revisions

February 18, 2025

Perhaps you have played Telephone—you whisper a phrase to one person, and by the time it reaches the last person in the line, it is hilariously mangled. Or maybe you have watched one of these Google Translate Sings videos before—after Google Translate takes song lyrics through some languages, Rick Astley famously sings “I’m not in love with my legs / You shine like salt and this is me…” I once asked ChatGPT to write an article in Chinese, then revise it a few times, thinking that it might make the result better. However, after three revisions, the article completely collapsed.

We all know that LLMs have biases. But what if instead of carefully measuring them, we set off a chain reaction of self-amplifying bias loops by feeding LLM outputs to LLMs, again and again and again?

That is exactly what I set out to explore, more systematically and rigorously this time, with OpenAI’s GPT-4o. I took the Wikipedia article on Generation Loss and subjected it to a game of LLM Telephone: 100 revisions where the prompt asked it to “rewrite”, and 100 revisions where the prompt asked it to “paraphrase”.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

Before looking at the results, let us study the quantitative attributes of the 50th and 100th revisions for both prompts against the original article.

Generation Loss is rated as “start-class” on Wikipedia, which means that it is mediocre by Wikipedia standards. There are definitely grammatical errors and odd style choices sprinkled throughout, but the article is a good mix of factual information and explanation. This variety of ideas allows us to examine the LLM’s effects on the article in more depth.

Four text attributes were measured for every paragraph: word count, sentence length, readability according to the Flesch-Kincaid scale, and syntactic complexity according to parse-tree depths. Type-token ratio was also measured but later ditched, because TTR is meant to be used for materials much longer than paragraphs. The parse-tree depth was measured with StanfordNLP’s Stanza, whose depth was found with a simple BFS on the neural-network-generated syntax tree.

What can we see here?

First, sentence length and syntactic complexity definitely decreased, and the changes were highly significant. The LLM-generated versions used shorter, simpler sentences compared to the original article. The word count also decreased significantly, although less dramatically. Readability scores also decreased, meaning lower grade-levels, but this was not consistent across all four LLM-generated versions.

The only attribute that showed a steady negative trend over generations was the word count, which was somewhat significant compared to prior generations within their groups (p<0.1).

However, other attributes were not significantly different across LLM-generated versions. From a quantitative perspective, the revisions seem to be converging—converging to a local minimum, a stable equilibrium where the LLM bias keeps the article from going anywhere else with this prompt.

Phrase Genealogy

More fascinating patterns emerge when we analyze how specific phrases appear, disappear, or persist across generations. LLMs—with their own bias—filters, promotes, and buries certain concepts over time.

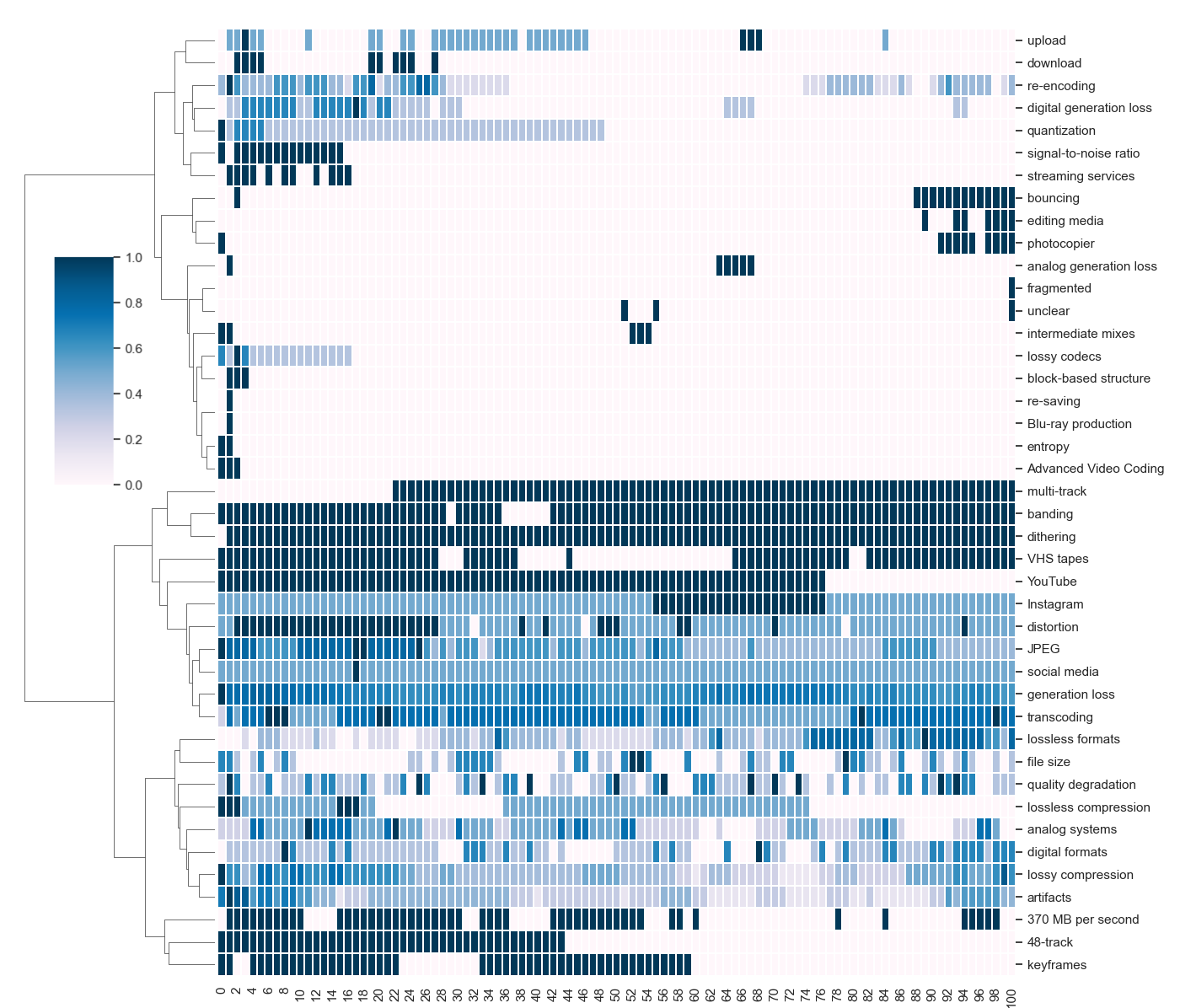

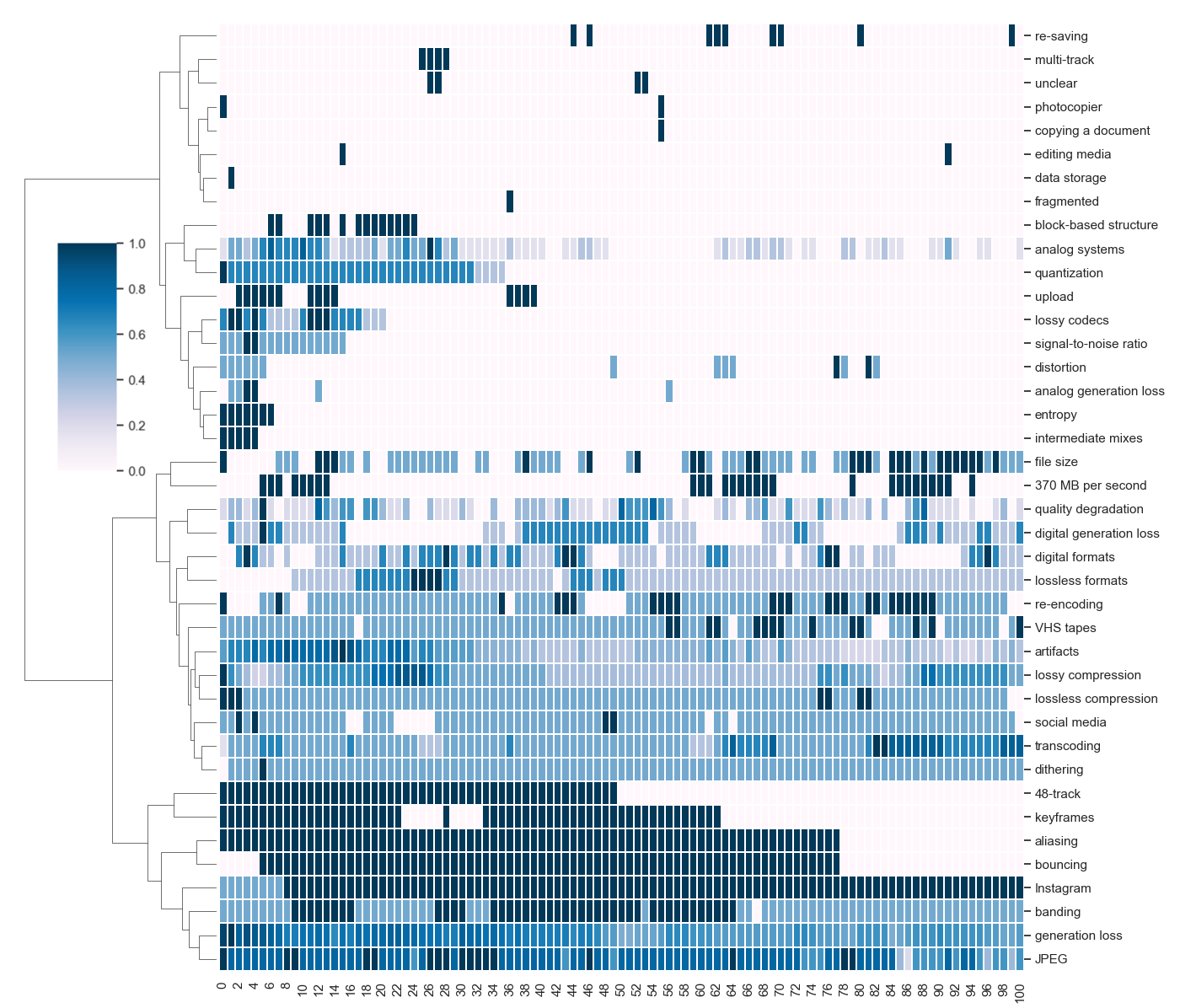

Let us take a look at two visualizations, for the two prompts, in the format of a clustered heatmap.

As you would expect, some technical terms vanished completely by the 100th generation, for example, phrases like quantization, aliasing, 48-track, and bouncing. Meanwhile, more consumer-friendly terms, like Instagram, distortion, and lossy compression persisted. Some phrases also appeared out of nowhere early, sometimes as early as the first generation, in the rewriting process, such as upload, dithering and 370 MB per second. Others reemerged after multiple iterations, such as lossless formats and digital editing media.

Thus, LLM rewrites are not just summarizing—they are reshaping the focus and relevance of different concepts. Subtly and bit by bit, the LLM reshaped the landscape of knowledge, reinforcing certain concepts while erasing others.

Wait, Am I Reading A Tech Blog?

Finally, let us move on to a more qualitative examination, and read a bit of these LLM-soaked writings.

By the 100th generation, the LLM outputs still explained generation loss. But by the 100th iteration, the details had started slipping away. The final rewrite confidently stated that generation loss is an unavoidable reality in analog media while misrepresenting digital degradation. The LLM also changed the focus of the article, framing generation loss as a digital preservation issue, drifting away from its broader technical definition.

In the age of analog media, generation loss was an unavoidable reality. Issues like signal degradation, background noise, and bandwidth restrictions contributed to diminishing quality.

In analog systems (including systems that use digital recording but make the copy over an analog connection), generation loss is mostly due to noise and bandwidth issues in cables, amplifiers, mixers, recording equipment and anything else between the source and the destination.

The tone also changed dramatically. The Wikipedia article had a neutral, encyclopedic style that was dry, technical, and sometimes redundant—almost like it was a Wikipedia article. The revisions were more journalistic and dramatic. They also took a more alarmist stance on lossy compression, almost warning about its dangers. In summary, the revisions read more like tech blogs instead of an article in an encyclopedia, either by dramatizing or by over-simplifying.

Whether working with analog or digital media, the principles for maintaining quality remain the same: start with high-quality originals, use minimal compression during production, and avoid excessive duplication or re-encoding. Adhering to these practices helps creators ensure their work retains its clarity and sharpness over time.

Successive generations of photocopies result in image distortion and degradation. Repeatedly downloading and then reposting / reuploading content to platforms such as Instagram or YouTube can result to noticeable quality degradation. Similar effects have been documented in copying of VHS tapes.

Apart from wording and tone, the LLM also restructured the content. The original article followed a straightforward and linear structure, while the rewrite improved readability by adding subtopics and breaking up large sections. The rewrites sometimes also merged sections together, making transitions smoother but losing the clear hierarchy. Overall, the rewrites were more engaging but subtly misleading—you can take a look for yourself:

Decoding Generation Loss: Causes, Effects, and Solutions / The Move to Digital Media: Improvements and Ongoing Issues / Overediting: A Shortcut to Generation Loss

Generation Loss / Digital Generation Loss / Editing

The Rise of Narrative Bias

One of the most striking trends in the LLM rewrites is the emergence of narrative bias. As you can see, the rewrites have more engaging, story-like structures. The once-neutral tone shifted to something with a sense of conflict and drama, speaking to a broader and more emotional audience. The LLM framed lossy compression as a villain and transcoding as a dangerous act—subjectivity and dramatization were introduced, although none existed before.

This kind of bias is not new. Humans have always gravitated toward storytelling, focusing on what engages and evokes emotion. I am writing this article only because there is an interesting (well, at least to me) story to tell. We select stories based on their narrative interest, such as conflict, resolution, transformation, or in this case, inspiring thought and discussion.

However, if you understand how LLMs are trained, you are probably aware that LLMs, with their vast arrays of sources, hold every opinion and no opinion. This is especially risky when you think about the potential for polarization. If massive corporations control the development of LLMs—which they do right now, as a matter of fact—this narrative bias will be influenced by their interests, whether those interests are for profit, influence, or ideological reasons. What could possibly go wrong?

Final Thoughts

Well, everything could go wrong. We might end up living in a world where the most compelling, attention-grabbing storylines dominate, rather than the most accurate or nuanced ones. As AI-generated content (which I do not agree with as a term here—it is somewhat misleading for the general population to call LLMs and diffusion models “intelligence”) becomes more and more ubiquitous, our collective story is changing. If AI reshapes not just Wikipedia but entire libraries, corpora, and archives, will we slowly lose the right to access fact-driven content because of the eventual flood of narrative-driven content?

From a structuralist perspective, which I am definitely biased toward, stories, constructed from language, are uniquely human. They are pinnacles of human thought and experience, driven by our need to understand the world around us. As machines learn to tame this format, do we really want networks of artificial weights and algorithms to decide our own story for us? Do we want every piece of content to spiral into a collective fantasy dreamed up by the biases of our time?

The dangers of AI-generated content could lie beyond alignment. Our narrative future is not just about what gets said and how stories are told, but ultimately, about who gets to decide the narrative.

mi tawa.